“ were just trying to verify whether he was telling the truth or whether these were skeletal remains of modern individuals that had gone missing or been killed,” Trammell says. The discovery of the human skeletal remains in Walters’s home reanimated old suspicions. As technology is changing, our rules are honestly shifting. That incident, which revolved around his insistence that he was owed money for his work on the cemetery relocation project, was apparently resolved when he returned 28 bodies and received $90,000 for his work.Īs an anthropologist, our job mostly in the past was focused on creating what we call a biological profile from the skeleton to help identify them. Louis to make room for transportation infrastructure in the city.

In the 1990s, Walters had been accused of stealing human remains that he was supposed to help relocate from a historic African American cemetery in St. Wheatley’s concerns only grew as he looked into the archaeologist’s background. “We didn’t want him trying to sell Native American bones,” Wheatley says. We wanted to make sure that they weren’t newer bones that had come across locally.” He added that there are several unmarked Native American burial sites in central Missouri and that there was a black market for items recovered from those sites.

He even produced decades-old documentation from the Guatemalan government to prove the legality of his cache.īut Wheatley says he “still wasn’t convinced that those documents covered those remains that we had seized. Walters argued that he had permission to own the skeletons contained in the coffins, saying that he had excavated the remains near Iztapa, Guatemala, sometime in the 1970s. “I’m not trained in anthropology or anything like that, so I didn’t know how old they were or what they were.” “We went ahead and secured them for safe keeping until we could figure out what was going on,” Wheatley says. The detective confiscated the coffins and their grisly contents. Wheatley called the Morgan Country Coroner, who indicated that the remains shouldn’t have been stored in Walters’s home.

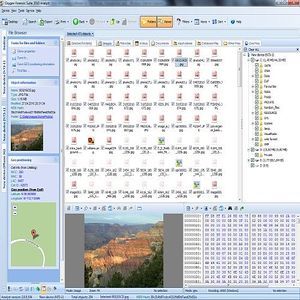

BLACKBAG FORENSICS COMPARED TO OXYGEN FORENSICS FULL

When they later reentered the home, they found four open wooden coffins full of human remains-bones, teeth, and skulls. The officers left the premises and applied for a search warrant. Wheatley says that he and his fellow officers did not find any people inside, but they did spy marijuana pipes in plain view. So they entered to ensure the safety of any occupants. Police knocked on the door of retired archaeologist Gary Rex Walters, but no one answered. Earlier that summer, Tony Wheatley, then a detective at the Morgan County Sheriff’s Office, went to a home just outside of Versailles, Missouri, to investigate a reported suicide attempt. “Just by looking at them, my inclination was that they were from different ancestral groups,” Trammell says. Those analyses indicated that some of the skulls bore characteristics of people with African ancestry while others did not. She photographed, inventoried, and measured the skeletal elements employing the standard biological techniques typically used by forensic anthropologists, who are still by and large not regular fixtures in crime labs. “There were different levels of preservation throughout the remains.” But others were in relatively good shape. Some of the bones looked ancient they were “falling apart,” Trammell recalls. Louis Medical Examiner’s Office as a jumble of bones inside four wooden coffins. It was the summer of 2014, and 15 skeletons had arrived at the St. COMPOSITE FROM ©ISTOCK.COM/K-KWANCHAi/MRTOM-UKįorensic anthropologist Lindsay Trammell had only just received the human remains and she already knew that she’d need help with this case.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)